I have heard that continuous glucose monitors (CGM) are becoming popular among individuals interested in their responses to diet, and their health risks.

In relation, this appears important:

A pre-proof from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

https://ajcn.nutrition.org/article/S0002-9165(25)00092-9/fulltext

Note, only one brand and model of CGM was used in the study. Significant variations in CGM values among different individuals tested under similar conditions were also observed. Some caution in generalizing findings is justified.

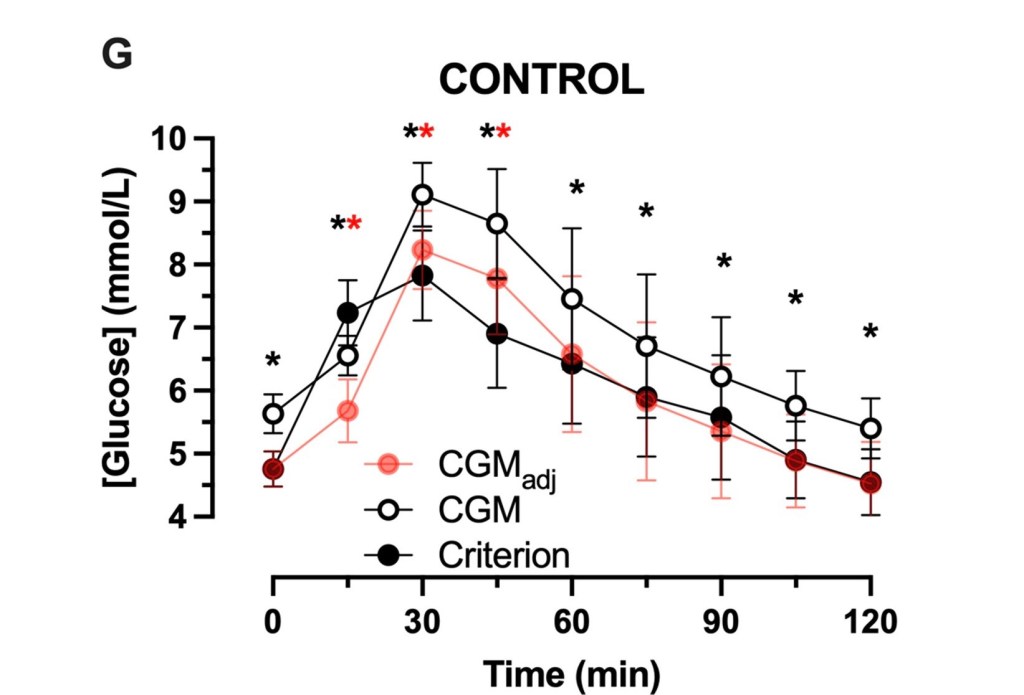

Thebgroup reports a mean overestimation by CGM versus capillary sampling as 0.9 mm/l, which is 16.2 mg/dl.

And this contributed to larger CGM calculated values for area, in area-under-the-curve calculations; e.g. the duration of hyperglycemia after a glucose challenge or a meal.

“CGM-estimated fasting and postprandial glucose concentrations were(mean±SD) 0.9±0.6 and 0.9±0.5 mmol/L higher than capillary estimates, respectively(both, p<0.001).”

“The increase in glucose concentrations measured with CGM versus the criterion method resulted in a >3.8-fold increase in the time spent above 7.8 mmol/L…”

“CGM overestimated glycemic responses in numerous contexts. At times this can mischaracterize the GI [glycemic index]. In addition, there is inter-individual heterogeneity of the accuracy of CGM to estimate fasting glucose concentrations. Correction for this difference reduces, but does not eliminate, postprandial overestimate of glycemia by CGM. Caution should be applied when inferring absolute or relative glycemic responses to foods using CGM, and capillary sampling should be prioritised for accurate quantification of glycemic response.”